Music educator Nigel Scaife explains how changing keys gives form, colour and tension to music – and why it’s crucial to understand the circle of fifths...

In part 6, we delved further into harmony, exploring common chord progressions and cadences – and discussing the importance of harmonic rhythm.

In this article we’re going to look at some of the ways composers typically move from one key to another – the process called modulation.

Most piano pieces start and end in the same ‘home’ key, but they usually modulate at some point, even if only for a short time. The process of modulation should not be a mysterious one that only composers grapple with, as understanding how the modulations work in the pieces you are learning gives you a better understanding of the music’s structure. This in turn helps you make the music more expressive in performance. The process of passing from one key to another adds interest, variety and contrast to music, as well as drama in many cases, so to convey these aspects fully the performer needs to grasp the tonal journey of the piece.

Modulation is a vital aspect of form in music. The process of changing key articulates structures such as binary, ternary and the more sophisticated sonata form, to name but a few. In order to fully establish a different key to the home key there has to be a perfect cadence in the new key, usually with a dominant seventh before the new tonic chord.

In binary form the first section starts in the tonic and moves to the dominant, with the second section starting in the dominant and working its way back to the tonic by the end. This AB form appears in many simple piano pieces, particularly Baroque dance movements. Studying the harmony of these pieces is a good way to start getting to grips with modulation.

The most common type of modulation is from the home key to what is known as one of the closely related keys. These are keys with a difference of no more than one sharp or flat in their key signature. All keys have five closely related keys and these can be found by looking at the circle of fifths diagram below. Taking any given key you will see that there are five keys surrounding it.

So, for example, taking Bb major you can see that it is surrounded by G minor (its relative minor), F major (dominant), D minor (relative of the dominant), Eb major (subdominant) and C minor (relative of the subdominant):

The most common modulation in major keys is undoubtedly to the dominant. In minor keys it is common to modulate to the relative major or dominant minor. It is worth noting that the five closely related keys form the diatonic major and minor triads of the home key (excluding the diminished triads):

Any keys which are not closely related to each other are said to be ‘remote’ or ‘distantly related’ and modulation to these keys is relatively less common as a consequence.

So how do we know when the music has modulated? As well as hearing the movement to the new key, we can usually find visual signs in the notation. For a new key to be fully established there must be a perfect cadence in the new key. This means that there is likely to be an increased use of accidentals (sharps and flats) within the music. These accidentals often give us a clue that there is a change in tonality. If, for example, we take C major as our home key, we can see that the dominant 7ths of the closely related keys all involve the use of an accidental:

There are three standard means of getting from one key to another. Firstly, there is what is called common chord modulation. This is where the process is made smooth by the use of one of more chords that are common to both the old key and the new key. Chords which are common to both keys and which are used to modulate are called pivot chords. These pivot chords straddle both keys and make the process seamless.

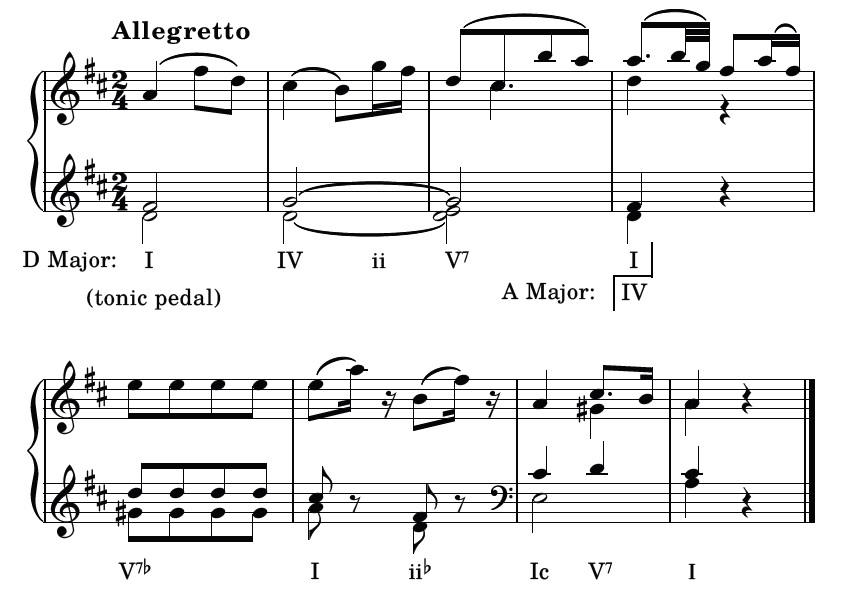

In the following example from Mozart’s Fantasie in D minor K397, the chord in bar 4 acts as a pivot, as it is both the tonic in the home key of this particular section, D major, and the subdominant of the key to which the music is about to modulate, A major. The chord in bar 5 is an E7 in first inversion. The introduction of the G# as an accidental in bar 5 alerts us to the fact that the music is moving away from the tonic key. It only fully arrives in the new key with the perfect cadence at the end of the example:

So pivot chords can be named in both old and new keys. Any given pair of related keys shares at least one diatonic chord in common which can provide the smooth transition. If we take the modulation from C major to its dominant, G major, we see that they share four common chords, any one of which may act as a pivot between the keys:

The most common pivot chords in a major key are ii or vi; in minor keys they are i or iv.

The second type of modulation is called abrupt modulation. As its name suggests, this is where there is a direct change of key without the use of an obvious pivot chord. In this type of modulation it is more likely that the key to which the music moves is not a closely related one. Abrupt modulation is far less common than the common-chord type of modulation.

The third type of modulation is through the use of chromatic chords. These are chords which contains a note or notes which do not belong to the prevailing key. Chromatic chords are used for their colour and for their dynamic quality which can help to propel the music forward. They are often written simply as interesting chords in their own right within a key, but they can also be used to modulate.

One of the most colourful of the many chromatic chords is the diminished 7th. This chord is made up of a series of minor thirds and has an unstable quality which gives it a distinctive sound. Here are some examples in Beethoven’s ‘Pathétique’ Sonata. Notice how the diminished 7th chords, shown by arrows, destablise the sense of key. They allow Beethoven to move from G minor to the following remote key of E minor at the start of the next Allegro section. The Eb spelling in the second bar of the example changes enharmonically to D# in the following bar, where the function of the diminished 7th changes and the key moves from the flat side of the circle of fifths to the sharp side:

If one note in a diminished 7th chord is taken down a semitone, then a dominant 7th chord is created. In this way a number of different keys can be reached with relative ease: a useful tool in the improviser’s toolbox!

When a chromatic chord effectively acts like a dominant it is called a secondary dominant (or sometimes an ‘applied dominant’). The chord that follows one of these will sound like a temporary tonic and therefore it is said to be ‘tonicized’. In other words it is momentarily established as a tonic without that tonic being fully established as a new key.

This brings us to the issue of what constitutes a modulation. Although the concept is relatively straightforward to grasp in principle, in reality it can be less clear-cut. Sometimes there might be only a brief change of key, in which

case it is usually called a ‘transient’ or ‘passing’ modulation. This variety within the world of modulation only reinforces the fact that music is such an endlessly fascinating art form to study, to analyse and to theorise about – and even better, to participate in.

Missed previous parts of the series? Check them out below:

About the author:

Nigel Scaife began his musical life as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral. He graduated from the Royal College of Music, where he studied with Yonty Solomon, receiving a Master’s in Performance Studies. He was awarded a doctorate from Oxford University and has subsequently had wide experience as a teacher, performer and writer on music.