What is Sonata Form?

A matter of form:

The Sonata

Pianist takes an offbeat look at the language of music – with the Sonata –

a form that often appears in the scores section of the magazine

Like any discipline, music has its own terminology. When you study music, you learn this terminology so you’ll be able to understand the printed score. With this knowledge, you’ll know when to play slowly, when to play loudly, when to add extra feeling and so on. The nomenclature of music takes a while to come to grips with, and – unfortunately for audience development managers everywhere – it’s also rather intimidating. In the audience of any classical concert, there will be many people who are passionate about music who never studied it and who will be mystified by the following kind of a passage in a programme note:

‘The first movement begins with a carefully worked opening theme, followed by a second theme in G major, which is threaded through an elaborate development section that ends with a recapitulation and a coda.’

It’s possible to enjoy the Mozart or Beethoven sonata as played by your favourite pianist without understanding this passage. But already knowing about the sonata form will certainly enhance your listening, playing and understanding.

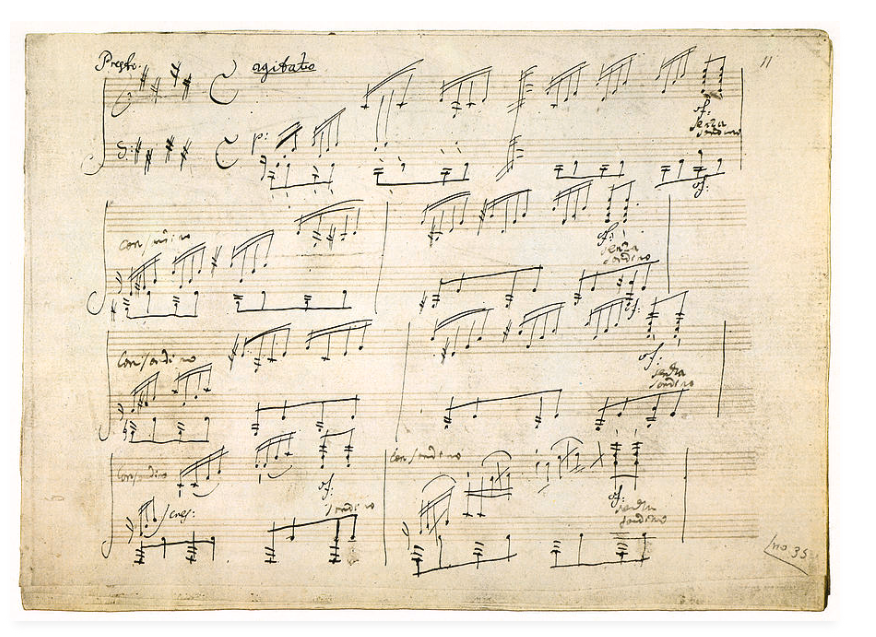

(Opening of Beethoven's Sonata Op 109)

The Sonata is one of the most famous of musical forms. It had its heyday in the Classical era, but the original meaning of ‘sonata’ was very different. It was a term for a played, in contrast to a sung, piece of music. The sonata form (also known as sonata-allegro or first movement form) may well have evolved from earlier two-part forms. In the 18th century, the form, as we now understand it, seems to have sprung up rather suddenly, much to the fascination of modern musicologists. In the Classical era, the sonata form was ‘the structural basis of most first movements, of overtures, and of many slow movements and finales’, in the words of musicologist Leonard Ratner. It was a loosely codified compositional form, reaching its apex in the instrumental sonatas, chamber music and symphonies of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven.

(Mozart at the piano with sister Nanerl, while father Leopold looks on)

We say ‘loosely codified’, because these three musical titans did not follow the same recipe every time they sat down to write a sonata. As Charles Rosen writes, ‘the “sonata” is not a definite form like a minuet, a da capo aria or a French overture: it is, like the fugue, a way of writing a feeling for proportion, direction and texture rather than a pattern.’

In fact, the study and analysis of the sonata form didn’t really get underway until the early 19th century, by which time the form no longer predominated. Carl Czerny (pictured below), in his School of Practical Composition (1848), was one of the first post-Classical era musicians to put into place an analytical framework for the sonata form. His status as a pupil of Beethoven may have helped promote his analysis, which puts the thematic material in the foreground and pushes melodic concerns to the background.

Rules of the game

It’s not that the ideas of Czerny and others of that period are wrong, as Rosen point out, but it’s more that this way of looking at the sonata form is imprecise. There are so many uses of the sonata form that don’t adhere to the supposed rules. What are those rules? Take apart a sonata movement using the theory book of your choice, and you will be given a variant of the following:

I. Exposition

II. Development

III. Recapitulation

IV. Coda

(The opening of Beethoven's furious 'Moonlight' finale movement)

The exposition begins in the tonic or ‘home key’ and will include one or more themes. There will be a transition, most often in the dominant key, which will take us into the development of the previously announced themes. After the themes have had a good workout, the exposition is reprised, though usually not exactly in the same way. A short post-script, the coda, might be added at the end.

To borrow an analogy from a teacher we met some time back, studying and playing music is like going on a journey, and a piece of music in sonata form is more directed journey than most. With sonata form, odds are good that you will end up more or less where you started, unlike, say, a fantasia, where you might start in Manchester and end up on Mars.

In the first part of the sonata, the exposition, you set out on your journey from your home to a single destination. For the sake of this story, we’ll say that Los Angeles is your home. It’s a familiar and comfortable place, the ‘home key’ that everyone wants to return to. Before you leave, you have given thought to what you hope to see on your trip. Perhaps you’ll focus on finding places where well-known writers lived or visiting famous roadside diners. These are themes that will be developed throughout your journey.

You may have some expectations about what the trip will be like, but invariably once you are underway things are not exactly what you expected. The themes you brought with you are transformed and developed in ways you might not have imagined – your search for writers’ homes turns into a search for musicians’ homes, for instance.

You arrive at last in New York City. You have many adventures there, but then it’s time at last to return home. You travel home via the same route – the recapitulation of the exposition – and yet this reverse journey is different. For one thing, you have been changed by your experiences. You pass by the same landmarks you saw on the way out, but you see them with fresh eyes. Back home, reinvigorated by your trip, you decide to make some changes, and in a coda, an additional episode that’s related to but not really an essential part of the story, you decide to move to San Francisco.

It’s a light-hearted analogy we’ve offered here, though no more far-fetched then some of analytical tools attacked by Charles Rosen in his Classical Style book. Despite this, Rosen pointed up the centrality of the sonata form to the Classical era he returned to it – with an entire book devoted to the sonata form!

Have a favourite sonata you’d like to see featured inside the pages of Pianist? Send an email to [email protected]

For further reading

Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style.

Leonard G Ratner

The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven

Charles Rosen

Faber

Sonata Form

Charles Rosen

Faber