Great Teachers – Gary Graffman

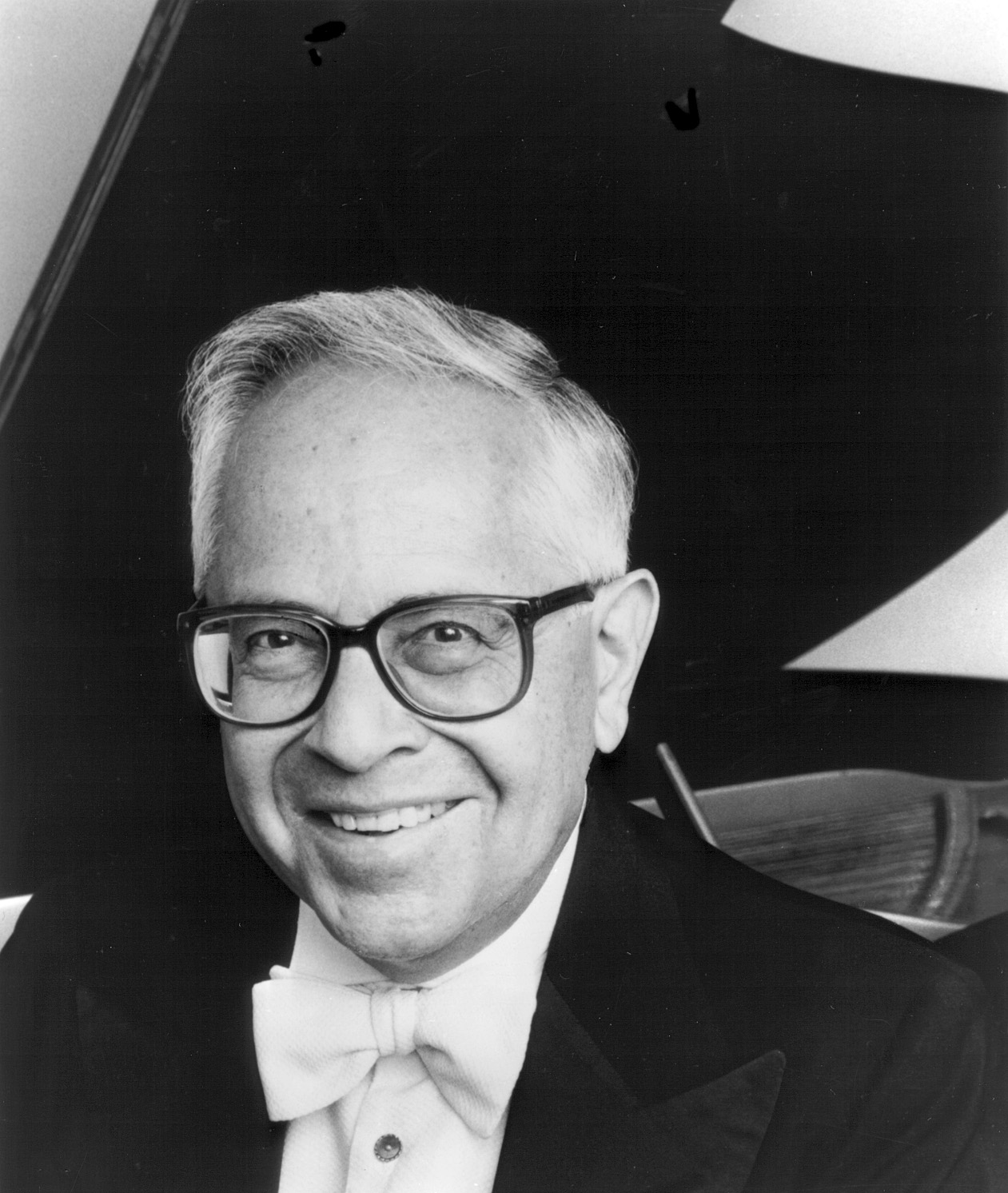

GARY GRAFFMAN

b. 1928

‘Gary helped me have an open heart,’ enthused Lang Lang, one of Gary Graffman’s most famous students in a recent interview. ‘He is just so knowledgeable about so much. He taught me repertoire, history, culture; he really expanded my understanding of the world.’ If it hadn’t been for Gary Graffman’s failure to show any significant talent on the violin at the age of three, he might not today be being praised by pupils such as Lang Lang – nor would he be regarded as one of the greatest pianists and most influential teachers of the 20th century, who was once described by the respected American music critic, Harold C Schonberg, as ‘the great architectural draftsman’ of contemporary pianists.

Graffman teaching a young Lang Lang

Born in New York City in 1928 to Russian immigrant parents, Graffman was switched to the piano by his violinist father, a student of Leopold Auer, after he found the violin unwieldy. By the age of seven, he found himself entering the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia as a student where he would study for 10 years with the redoubtable Russian pedagogue, Isabelle Vengerova. He became the director of the Curtis Institute 50 years later after he first walked through its doors.

Leaving Curtis as a young virtuoso on the cusp of a brilliant career, Graffman’s pianistic prowess was further honed by private studies with Vladimir Horowitz (indeed, Horowitz limited his teaching to only a few of the most talented, and later acknowledged only Byron Janis, Ronald Turini and Graffman as having studied with him) and Rudolph Serkin. These two pianists provided the young Graffman with a performing tradition from opposite ends of the musical spectrum. While Horowitz was steeped in the fiery virtuosity of the Russian tradition, Serkin’s was a more calming one, with an emphasis on the Austro-German repertoire and a very strict faithfulness to the score.

Since winning the famous Leventritt Award in 1949, Graffman has been an almost permanent fixture on the concert platform, performing with many of the great orchestras and conductors (Bernstein, Mehta, Ormandy and Szell) around the world. In 1979, however, he suffered an injury to his right hand, which may have triggered the resulting focal dystonia (his great friend, the late Leon Fleisher, suffered a similar fate), and for the best part of 30 years he has had to concentrate on his beloved teaching commitments and the repertoire for left hand alone.

Role model

So what makes Graffman special as a teacher? As one of his very first students, the American-based, Philadelphian-born pianist Lydia Artymiw (who came third in the Leeds competition in 1978) is probably best placed to comment, having studied privately with him for 12 years. ‘Mr Graffman was very critical of my playing, demanding the highest standards all the time,’ she says. ‘But he also had a wonderful sense of humour. While he has many amazing attributes, he always treats his students as young professionals, serving not only as a great role model to them but also as an important mentor. He helped me and many of his students obtain professional management, arranged auditions for important conductors, and, moreover, was incredibly generous with his time and his efforts.’

Graffman pupil, Lydia Artymiw

Artymiw’s former teacher, Freda Pastor Berkowitz, who knew Graffman well, introduced her to Graffman. She remembers her very first lesson with ‘Gary’, especially as it occurred on the day of her 13th birthday. ‘For my first lesson (nearly two hours), I played the complete F major Beethoven Sonata opus 10 no 2, the Chopin “Black Key” and the “Revolutionary” studies. Then, over the years, I studied a large number of big works like the first, third and fifth Beethoven concertos, the Brahms D minor, the Chopin E minor, as well as the Rachmaninov first and second concertos. There was a great deal of solo repertoire too.’

Lessons for Artymiw were never weekly, as Graffman was far too busy with 100 concerts annually during those early years. And the length of those lessons when she did have them? ‘They were usually about 90 minutes, sometimes continuing for two hours, either in Philadelphia or at his apartment in New York, and lessons varied from one to two times per month. During those periods when he was away concertising, he arranged for me to play occasionally for his dear friend and colleague, Dr Piero Weiss (also a very inspiring teacher who taught at Columbia University in New York), ensuring that my lessons could continue without long breaks.’

Expectations in the lessons were high, Artymiw says. ‘I was asked to have a sonata or concerto completely ready and memorised for the first lesson. Mr Graffman always listened to each movement all the way through, then tore it apart while we worked in the greatest detail. His extraordinary perfect pitch and quick response meant that he heard everything, and it was virtually impossible to play a wrong note and get away with it!’

Sometimes Graffman would recall what Horowitz had said during their lessons and would give advice based on Horowitz’s insights into the music (or technical solutions to certain problems). ‘When I brought Rachmaninov No 2 to him, he remarked that he had performed it several hundred times and that he played it very differently. He then continued: “But now we need to work on it and make your interpretation more convincing.’”

As for a particular ‘method’ of teaching, neither Artymiw nor two other Curtis students, Di Wu and Ignat Solzhenitsyn, heard him speak of one. ‘Though if you had to say something about his teaching in general,’ says Solzhenitsyn, a Russian-American pianist and conductor, ‘it would have to be his emphasis on listening better. He was always saying, “Why is this uneven?” or “Why do you pedal so much here?” He would often ask my reason for a given choice of tempo or interpretation. It seems to me that he felt that many choices were possible, as long as they were backed up by strong logic.’

While Graffman didn’t ask his students to produce a particular sound, Solzhenitsyn recalls how he was often challenged to voice more subtly, or to produce a more vibrant colour. ‘I remember studying Rachmaninov’s ‘Corelli’ Variations, which I had never heard until Graffman suggested I learn them. I always think of the vivid imagination for sound he had in this piece (as in so many others), and his insistence that its not insignificant technical demands be placed at the service of the musical concept.’

For Artymiw, Graffman always orchestrated the piano. ‘This left-hand melody should sound like a cello, the right hand like an oboe, or this voice like a horn, and so on. So, the combination of producing orchestral sonorities on the piano, plus cultivating a singing tone (most important for me), were my main goals.’

Alongside all these other qualities, Artymiw points out Graffman’s incredible wealth of performing experience, which gave him tremendous insights into actual performing issues. ‘When the French horn has an important solo towards the end of the exposition in the first movement of the Brahms D minor Concerto, he pointed out that I should be completely aware of the breathing, as my entrance might have to be delayed slightly in order to be together with the horn. Moreover, he always noted where it was important to have eye contact with the conductor.’

As Chinese-born pianist Di Wu said a few years back, ‘Gary is like a grandfather to me. When he doesn’t hear from me for some time, he calls me to find out how I am, to check that I’m still alive or something, or to find out if I have a boyfriend. After a lesson, when we’re not discussing musical details in a Rachmaninov score, for example, we might go out for a walk or some dinner. He can eat and drink more than I do, walk faster than I do, and he never suffers the consequences like I do,’ she laughs. ‘I have no idea where he gets all his energy from. Musically speaking, he gives me the creative freedom to be who I am, which is why all his students are so different. He’s not looking from his perspective, saying, “I want this to be like this… etc”, because he’s encouraging individuality. It’s not what you get from many other teachers.’

© Christian Steiner

Teacher file

GARY GRAFFMAN

FAMOUS STUDENTS

Lang Lang, Yuja Wang, Lydia Artymiw, Ignat Solzhenitsyn, Di Wu, Haochen Zhang, Robert McDonald

RECORDINGS

Highly acclaimed recordings for Columbia (CBS) and RCA of Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Brahms, Chopin and Beethoven concertos

FILMS

There are no films that we know of on Graffman, but if you type his name into YouTube, you’ll find an array of interesting footage and recordings

TEACHING

Joined piano faculty of Curtis Institute of Music in 1980, becoming director in 1986 and president from 1995 until 2006

BOOKS

Author of highly praised memoir, I Really Should be Practicing (New York, 1981)

TRIVIA

Graffman was a judge at the Miss United States beauty contest and performed Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue on the soundtrack of Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979)

© Christian Steiner (main image)