30 November 2024

|

Like anything else, improving one's sight-reading skills is a matter of practice. Here's advice from our expert piano teachers

Good sight-readers are born, not made – there’s a statement that will instantly spark discussion, if not outright argument, among any group of musicians! But whether it’s true (or not) that sight-reading is an innate ability, it does not mean that you cannot improve your own sight-reading, whatever your level. Practising sight-reading is the best way to get better at it, and there are skills you can develop that will help. In this article, we will look at some general ways to practise your sight-reading and then we will take up a few examples of pieces that appeared in past issues of Pianist. Note: We strongly advise that in order to practise your sight-reading, you always work from something below your own level or even a level below that.

Be a detective

With the music in front of you but before you attempt to play, look very closely all the information that’s on the page. Piano students should try to play at being a kind of musical detective, taking in as much information as possible before they begin to read through a piece. Look at the time signature, the key signature, the tempo markings, the dynamic markings, the phrasing, the rhythm, the fingering (if any) and so on. Perhaps most importantly of all, try to develop your inner ear, aiming to hear as much of the music as possible in your head before you play a single note. While you do not have to be able to hear everything at an exact pitch, you can still, with patience, manage to get some kind of idea how the music should sound when played.

Rhythm

Rhythm is perhaps the most important element of sight-reading practice. We recommend that you tap out the basic rhythms before you play. Start with single hands first, or perhaps with a single tricky bar, and then tap out both hands together. Tap exactly what you will play. There is an element of coordination involved, but this is all part of the sight-reading process. Tap the rhythms extremely slowly, counting aloud as you play. If it’s a long piece, you can just work through the typical rhythmic patterns of it (no need to tap it all the way through!) and look for the difficult rhythmic parts. Once you’ve tapped your way through the rhythms, go to the piano and chose a single note in the RH and a single note in LH and just tap out the rhythm on the single key (hands separately first, and then hands together). Once you’ve done that, play through the first line.

Counting

One trick a teacher of ours learned a while back from an excellent sight-reader is to stretch out the counting when you encounter something difficult. What we mean by this is that you must to keep counting at all costs, but to slow down your counting when you come across something difficult. So you might start counting with ‘1 and 2 and 3’ at a slow, steady pace, but then at the difficult part, slow down to ‘1… and… 2… … and… … 3… …’, which gives you a chance to see what is coming next. The vital thing is to keep going, without stopping completely. The worst thing you can do in your sight-reading practice is to stop. Once you stop or pick up the hands to go back over something you have missed, you lose the overall sense of rhythm, and more often than not, lose your place on the music. Your goal is to continue to count, without stopping, but stretch out the hard parts.

Intervals

After the rhythm, reading by musical interval (e.g. seconds, thirds, fourths and fifths) is the next most important skill. We often tell piano students to look at the intervals and not worry so much about the names of the notes themselves. This is especially important when the music extends beyond the stave, and you get very high notes in the right hand or very low notes in the left.

Harmony

Then there is the harmonic outline of the music itself. You don’t have to know every single note or chord of everything you play, but having a basic awareness of what you are playing does help you a great deal. Remember that the harmony in music is from the bottom up, and that is the best way to sight-read a difficult chord for instance, is by working up the musical stave.

Fingering

Fingering is important too, so if a fingering is not marked in the score, try to accommodate as many notes as you can in the same hand position, to avoid any unnecessary change of hand position. Try to keep your eyes on the score at all times, imagining that your fingers are sticking to the keys, feeling their ways towards the next notes. It’s difficult to do, but you should always try to look at least one bar ahead. If the music involves a leap of any kind, try to exercise a degree of peripheral vision. But by all means look at the keyboard if you really have to.

Sight-reading examples

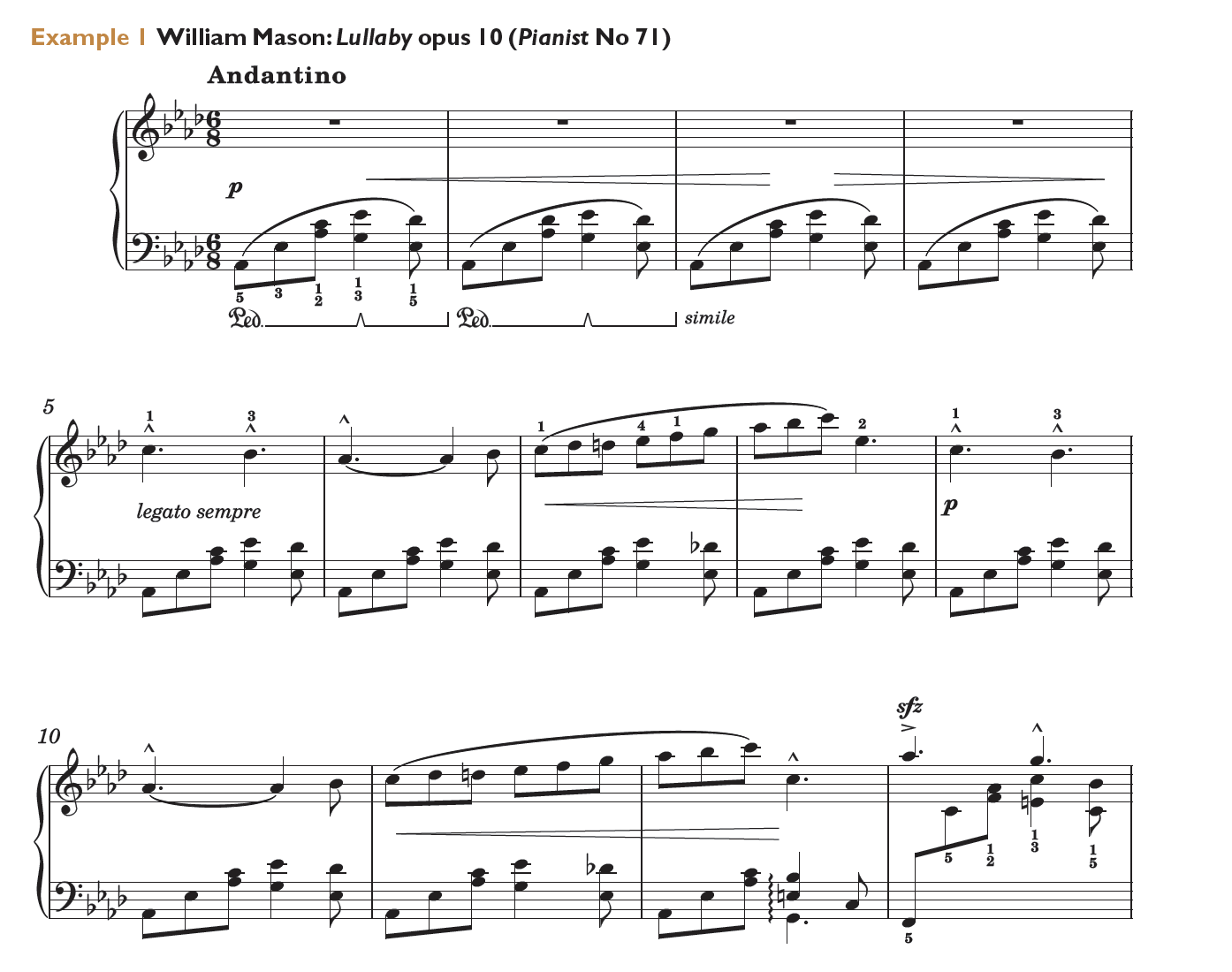

Bearing in mind what we've covered above, here are several musical examples from past issues of Pianist that illustrate a few sight-reading approaches you can apply to any piece. In the first 12 bars from the opening of Lullaby opus 10 by William Mason (issue 71; below), notice how the LH figurations from bars 1-12 are almost identical. You’ll see there’s the change of chord on the third quaver beat in bar 2 and that there’s a change in the RH melody between bars 7-8 and bars 11-12. Study the fingering in bar 1: it can be applied to all the bars where the figurations are basically the same. You’ll have already considered the range of notes (what I call ‘musical mapping’) from the lowest notes in each bar to the highest. Having an awareness of the range of notes within a bar (and beyond) is really helpful.

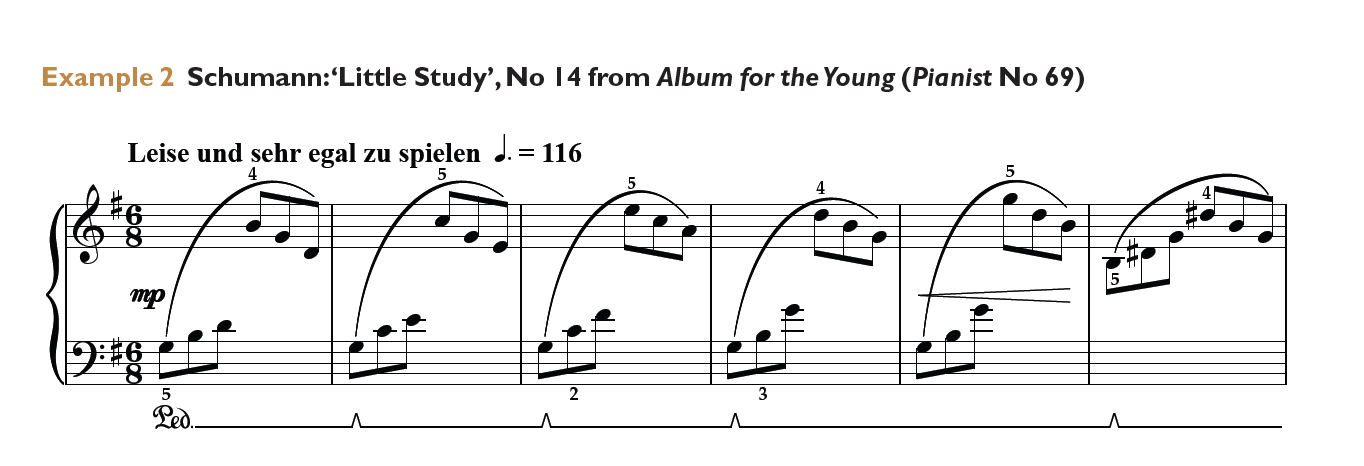

Where you find figurations similar to Schumann’s Little Study, published inside Pianist No 69, practise each bar in block chords. Again, try to use the published fingering, looking for the subtle differences in the harmonies and the intervallic distances between the notes themselves. Looking at the LH in bars 1-4, for instance, you will see that the first chord, from the bottom note up, has intervals of a third and a third, the second chord has an interval of a fourth and a third, and the third bar a fourth and a fourth – and so on. Think in terms of lines and space notes. A line note to a line note is a third, a space note to a space note is a third, and so on.

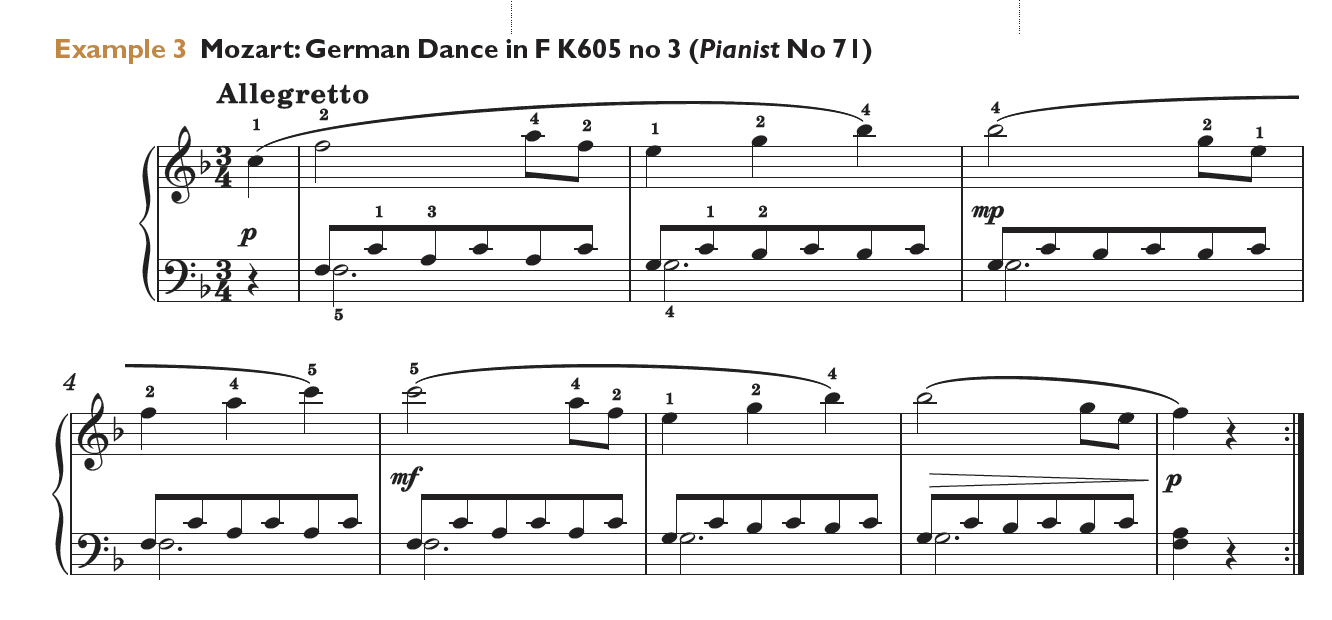

You can apply the same block chord technique to the LH (bars 1-16) in Haydn’s Gypsy Dance, and again to the LH (bars 1-13) in Mozart’s German Dance (both pieces from issue 71). Any figuration like the LH in this Mozart excerpt below can be practised in the same way, by playing the first three notes of each bar together as a block, holding them down for a whole bar of three beats. You could also just practise one chord per bar.

While there are plenty of books on sight-reading out there, don’t limit your reading just to that. Picking up all kinds of music will help your reading no end, be it jazz, popular or classical. And don’t forget all those duets too. Often, having to play through a score with another musician who happens to be a better sight-reader than you can also be a great help. Good luck.

TO SUMMARISE...

1. Take in as much information as you can before you begin, including time signature, key signature, tempo markings, dynamic markings, phrasing, rhythm and fingering.

2. Be aware of the range of notes within any given bar. Make a quick mental ‘musical map’ of the lowest notes in each bar to the highest.

3. Keep going! Slow down the tricky bits if you have to, but do your best to avoid coming to a complete halt.

4. Focus on reading by the intervals rather than worrying so much about the names of the notes.

5. Play with others. When you’re reading through a piano duet or a violin-piano sonata, you have to keep going – your partner is relying on you!

FURTHER READING:

5 TOP SIGHT-READING BOOKS

ABRSM Joining the Dots

Trinity Sight-Reading Piano

Faber Improve your sight-reading (Paul Harris)

Schott Piano Sight-Reading (John Kember)

Alfred Basic Piano Library Sight-Reading

Join Pianist Prime today in order to view archive issues of Pianist – which means hundreds of scores – all the way back to 2010.