14 January 2026

|

When Alfred Brendel passed away in June last year, an outpouring of tributes commemorated one of our century’s greatest artists whose erudite, authoritative mastery of the Classical canon defined and influenced musical interpretation to a level that few contemporaries have matched. Melissa Khong pays tribute.

For many critics and fans alike, Alfred Brendel was the ‘thinking man’s pianist’. A truly iconic figure, the man with inquisitive eyes and a secret smile peered out from the covers of CD-box set by Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn and Schubert. His recordings were always convincing – whether he was playing solo or alongside such artists as Zubin Mehta, Simon Rattle, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Matthias Goerne. He remained an active presence in the cultural sphere – speaking on stage, giving masterclasses or sitting unassumingly in the audience well after his last public performance in 2008.

Much has been said about Brendel’s vast discography (three Beethoven sonata cycles among over 100 albums), his virtuosic pen (from which flowed probing musical analysis and nonsensical poems alike), and his wealth of interests spanning Baroque architecture to Gary Larson cartoons and arthouse cinema. Indeed, so much has already been said and repeated by others that it seems only fair to let Alfred Brendel tell his own story again – something which is possible, thanks to the abundance of writings, recordings and musings that he has left behind.

Once upon a time

I was no wunderkind

Due to my obstinacy

though

I became one later

No easy task

stretching yourself

yet remaining under five foot six

for the sailor-suit still to fit

Thus begins, in typical Brendel fashion, one of his poems from Cursing Bagels, a collection of deliciously-irreverent poems published in 2004. The tongue-in-cheek verse, certainly not to be taken too seriously, does however reveal a few glimmers of autobiographical truth. ‘I was not a child prodigy,’ Brendel often insisted, before recounting his rather atypical start. ‘My parents were not musicians. There was no music in the house. I had a good memory but not a phenomenal one. I was not a good sight-reader,’ he confided in Mark Kidel’s documentary Man and Mask, adding that ‘I am completely at a loss to explain why I made it!’ While the documentary’s credits roll, an old photo shows a cheery Alfred, age around ten years old, wearing a sailor suit, surrounded by other children and beaming at the camera.

At home with Minnie

The only child of German-speaking parents with Austrian, Italian and Slavic origins, Brendel left his native Moravia at an early age and – due to the various professions his father held – spent his childhood travelling through Yugoslavia and Austria. His family’s most tangible link to music was, as Brendel enjoyed quipping, his grandfather teaching Gustav and Alma Mahler to ride a penny-farthing at his cycling school. As for Alfred, his initiation to music began with singing – first through songs taught to him by his nanny, then from singing along to operetta tunes that wafted out from the gramophone at his father’s hotel on the island of Krk in the Adriatic Sea. Later, in Zagreb and Graz, the young Alfred started taking piano lessons. His first teacher strengthened his fingers; the second told him he needed to relax. ‘She did not say how, but it was interesting to figure it out myself,’ remarked Brendel, who ‘got used to finding things out for myself, a state of affairs that would become permanent.’

After the war, the teenage Brendel returned to Styria in the southeast of Austria, which he had fled during the Russian army’s occupation, and it was there that he made up for lost time: ‘I composed, drew and painted, wrote sonnets and practiced the piano. And I read a great deal.’ At the age of 17 he gave his first recital, naming it ‘The Fugue in Piano Literature’ – an ambitious programme comprising solely of works with fugues ‘that would have frightened me in later years.’ At his first recital, which featured a sonata he composed (‘with a double fugue, of course!’), Brendel also exhibited some of his paintings, which he told a friend to subsequently destroy. Fortunately, the good friend did not.

'My curiosity for everything that is new in art has stayed with me throughout my life'

Brendel often expressed an underlying frustration and regret over the lack of artists and intellectuals in his family. ‘My parents were loving and reliable – that counts for a lot. For the rest, there wasn’t too much that we had in common,’ he conceded, speaking quite openly about his need for emancipation. ‘I had to free myself in many ways from my parents because they were not really aesthetically-minded or intellectual. If it is necessary for a young person to put into question everything he has learnt from his parents, I think I did it quite well.’

The image of the intellectual which he cultivated during his teenage years and onwards – from the bespectacled gaze to his philosophical approach to music and other artistic pursuits – was undoubtedly a mark of independence and a product of the epoch’s cultural spirit, far more than that of his upbringing. Living in post-war Graz [the capital of Styria] would have a decisive impact on Brendel’s outlook: ‘It was an exciting time as all of the contemporary art that had been inaccessible gradually surfaced. My curiosity for everything that is new in art has stayed with me throughout my life.’

An avid collector of diverse objects ranging from death masks to tribal sculptures and items of kitsch, Brendel displayed a particular affinity with uncommon ideas and novel approaches, an aesthetic practice that found as much resonance with the German Romantics of the early 19th-century as it did with the Dada avant-gardists 100 years later. Gothic architecture fascinated him, as did fantastical creatures, fables and myths: ‘I’m fond of monsters if they belong to the imagination, and of course rather frightened of them if they are human.’

As much as he strove to distinguish himself from his family’s social environment, his father was the one who introduced Brendel to the world of cinema. As a young boy in Zagreb, Brendel regularly attended film screenings at the Capitol, a large cinema run by his father. ‘Some were very entertaining; I laughed my head off,’ Brendel remembered. ‘Others, German propaganda, were quite horrible.’ Thus grew his love for cinema, particularly the dark-comedy and experimental films of Luis Buñuel, René Clément, Woody Allen, Jane Campion and Ingmar Bergman. Much later, when Brendel retired from the concert platform, he would curate seasons for European film festivals, always on the theme of laughter and dread – that near dyadic conflict which related to his early exposure to the screen. Writing poetry came ‘as a surprise, on a plane to Japan when I couldn’t sleep.’ Two collections of poetry, One Finger Too Many and Cursing Bagels, brimmed with mischievous phrases, nonsensical turns and subversive jibes. Just one example:

The Coughers of Cologne

have joined forces with the Cologne Clappers

and established the Cough and Clap Society

a non-profit-making organisation

whose aim it is

to guarantee each concert-goer's right

to cough and applaud

Brendel’s dizzying array of interests, passions and hobbies stemmed from his insatiable appetite for creativity, his enjoyment of opposition and duality (he liked musing about the usefulness of a doppelgänger) and the conviction that, as a musician, he needed to be nurtured through a rich, artistic prism. ‘It’s all part of my aesthetic food, really,’ said Brendel, who could just as easily tame his pen to write serious essays of intellectual depth and shrewd analysis. His two collections of essays, Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts and Music Sounded Out, have become sources of reference for musicians and musicologist alike.

'I was never part of an institution. I value my freedom'

For Brendel, three pianists mattered: Edwin Fischer, Alfred Cortot and Wilhelm Kempff. ‘Magicians of immediacy,’ he called them, ‘and great masters of sound and cantabile.’ Of the three, Brendel only had direct contact with Fischer, for whom he auditioned on the advice of his second teacher, and who told the then-16-year-old student that he should continue studying the piano on his own.

Brendel took part in a few of Fischer’s masterclasses in Lucerne and also studied briefly with Edward Stuermann, the sole exceptions to an otherwise autodidactic journey. The ‘encounter’ with Fischer would have a long-lasting impact on Brendel, who remembered the Swiss pianist as ‘anything but a perfect pianist in the academic sense,’ underlining instead Fischer’s ‘fabulous richness of expression, his marvellously full, floating tone, which retained its roundness even at climatic, explosive moments, and remained singing and sustained in the most unbelievable pianissimo.’

Cortot, on the other hand, impressed Brendel with his captivating shifts of character and atmosphere, splendidly achieved in Chopin’s 24 Préludes, ‘as if a kaleidoscope was shaken and a new constellation was instantly there.’ As for Kempff, ‘when he played, a veil was lifted from the soul. You witnessed a combination of seraphic simplicity, refinement and nervous turmoil.’

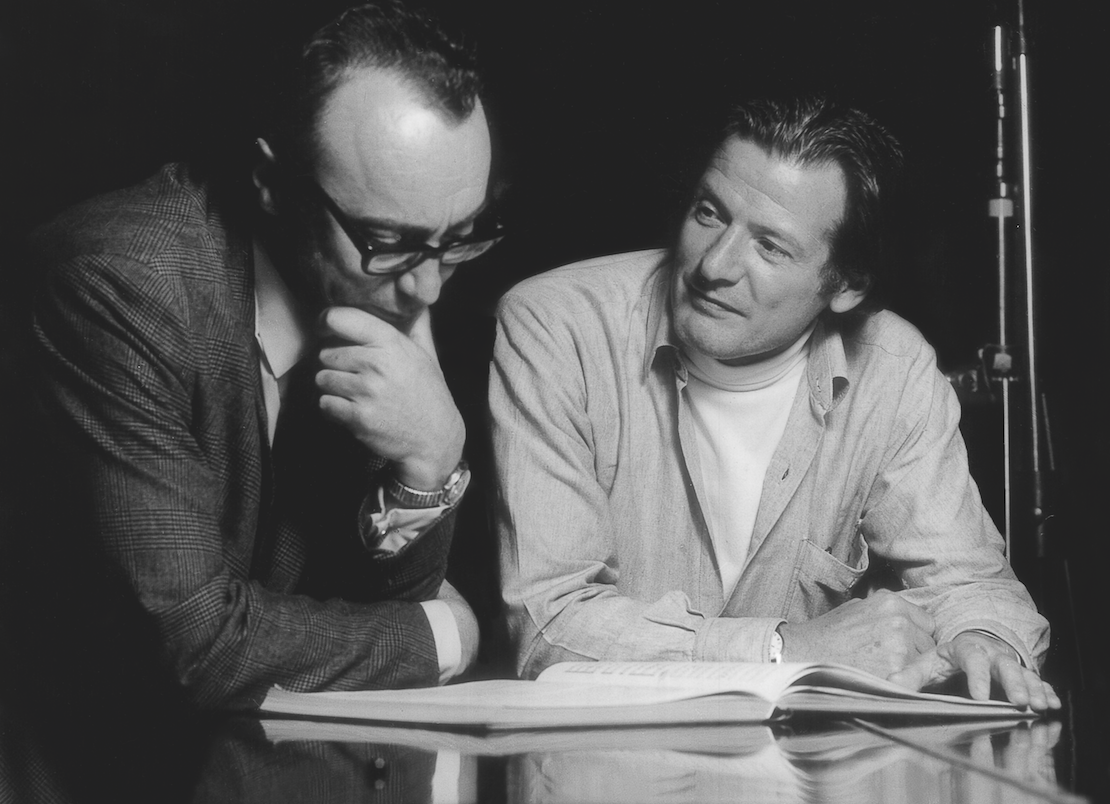

With Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Bernard Haitink

Sir Neville Marriner

These were the artists who – like Wilhelm Furtwängler, Otto Klemperer and Bruno Walter – as he specifically mentioned, ‘did not dissect but bind the components together,’ creating wider musical contexts to show how the first note leads to the last. Brendel clearly shared this philosophy, shaping his own musical thought via a profound knowledge of the harmonic, technical and historical framework of the works he played, while absorbing inspiration and enlightenment from other repertoire. Of notable influence were the lied [songs], which he performed regularly throughout his career, and the string quartet, which he enjoyed coaching after he stopped performing. One thing was for sure – he was not an academic nor part of an institution. ‘I value my freedom,’ he declared on several occasions.

'In all good music, feeling and intellect have to go together'

Brendel’s interpretations were very much a part of his aesthetic DNA, nourished by an inexhaustible reservoir of art and ideas. His aforementioned debut recital affirmed his attraction to complexity, further reiterated by the first recordings he made for SPA Records, a small American label. Busoni’s sprawling Fantasia Contrappuntistica was among the pieces Brendel recorded in the early 1950s, while his first solo LP recording contained the full cycle of Liszt’s little-known Weihnachtsbaum, rarely performed even today.

In fact, Brendel was one of the first pianists to champion the works of Liszt and to recognise the composer’s artistic value in face of the glitzy stereotype that long misled many scholars. ‘One has to take Liszt seriously in order to play him well,’ advised Brendel, who admired the all-encompassing spirit that Liszt embodied during his lifetime — as pianist, composer, editor, transcriber, philanthropist and devout Catholic. The dramatic depth and architectural unity Brendel brought to Liszt would become the hallmark of his Beethoven interpretations.

While his choice of tempi and phrasing highlighted a clear preference for control and logic, the brilliance of his performances came from the crafted characterisation of themes, allowing us to hear Beethoven at his most lyrical, grandiose, noble and introspective. Brendel’s Mozart was astonishingly fiery, full-bodied and expressive while Haydn offered an ideal canvas for his brand of imaginative wit, the pianist adapting his articulation to bring out the sparkling energy of the sonatas.

Brendel devoted himself to cycles, performing the Beethoven sonata cycle 32 times, but he also invested equally in Mozart’s concertos and Schubert’s piano works. Brendel the intellect helped elevate Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto to broader recognition. Brendel the virtuoso – for he was indeed one – elevated the inner tumult of Liszt’s and Schumann’s works and even relished in pure pianistic delight early in his career with a rather un-Brendelian programme featuring Balakirev’s Islamey, Stravinsky’s Three Movements from Petrushka and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Repertoire-wise, Brendel was, above all, surprisingly paradoxical: He could master an enormous amount of works, yet he had an intentionally-selective repertoire, focusing essentially on a handful of major Classical and Romantic composers. And even if he was open to different expressions of art, from Dadaism to kitsch, he could not stomach Grieg or Rachmaninov.

With James VanDemark and members of the Cleveland Quartet recording Schubert's 'The Trout'

Yet, this all fits in perfectly with his aesthetics and his fondness of contradiction. ‘One needs gravitas and lightness,’ he once said. ‘In all good music, feeling and intellect have to go together,’ he mused on another occasion. One of his favourite sayings was the mind-boggling aphorism by Jean Paul that ‘Humour is the sublime in reverse.’ Brendel also recognised the impossible psychological state of a performer. ‘I have to let myself go and control myself at the same time. I have to imagine what I’m going to do and, at the same time, listen to what I have done and react to it. It needs a split personality on many levels.’

Intellect, humour and curiosity made Alfred Brendel the multi-faceted artist he was: pianist, poet, painter, writer, speaker, mentor, cinephile, laughaholic and life-long learner. But at the end of the day, he was just a wonderful human being.

This article appeared inside Pianist issue 146

Images: Main: © Clive Barda / Decca; © Mike Evans / Decca (Marriner and 'The Trout); © Decca (all others)